Melatonin actions in the heart; more than a hormone

Melatonin and heart

Abstract

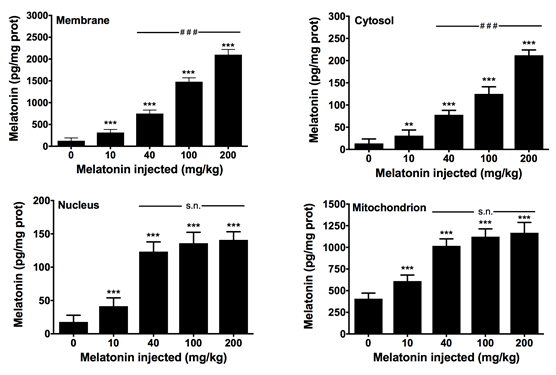

Due to the broad distribution of extrapineal melatonin in multiple organs and tissues, we analyzed the presence and subcellular distribution of the indoleamine in the heart of rats. Groups of sham-operated and pinealectomized rats were sacrificed at different times along the day, and the melatonin content in myocardial cell membranes, cytosol, nuclei and mitochondria, were measured. Other groups of control animals were treated with different doses of melatonin to monitor its intracellular distribution. The results show that melatonin levels in the cell membrane, cytosol, nucleus, and mitochondria vary along the day, without showing a circadian rhythm. Pinealectomized animals trend to show higher values than sham-operated rats. Exogenous administration of melatonin yields its accumulation in a dose-dependent manner in all subcellular compartments analyzed, with maximal concentrations found in cell membranes at doses of 200 mg/kg bw melatonin. Interestingly, at dose of 40 mg/kg b.w, maximal concentration of melatonin was reached in the nucleus and mitochondrion. The results confirm previous data in other rat tissues including liver and brain, and support that melatonin is not uniformly distributed in the cell, whereas high doses of melatonin may be required for therapeutic purposes.

References

2. Mackenzie SM, Connell JM, & Davies E (2012) Non-adrenal synthesis of aldosterone: a realitcheck. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 350: 163-167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mce.2011.06.026.

3. Slight SH, Joseph J, Ganjam VK, & Weber KT (1999) Extra-adrenal mineralocorticoids andcardiovascular tissue. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 31: 1175-1184. https://doi.org/10.1006/jmcc.1999.0963.

4. Gallego-Colon E, et al. (2015) Cardiac-restricted IGF-1Ea overexpression reduces the early accumulation of inflammatory myeloid cells and mediates expression of extracellular matrix remodelling genes after myocardial infarction. mediators Inflamm. 2015: 484357. http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/484357.

5. Arnold S, Goglia F, & Kadenbach B (1998) 3,5-Diiodothyronine binds to subunit Va of cytochrome-c oxidase and abolishes the allosteric inhibition of respiration by ATP. Eur. j. Biochem. 252: 325-330. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2520325.x.

6. Venegas C, et al. (2012) Extrapineal melatonin: analysis of its subcellular distribution and daily fluctuations. J. Pineal Res. 52:217-227. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-079X.2011.00931.x.

7. Jockers R, et al. (2016) Update on melatonin receptors: IUPHAR Review 20. Br J Pharmacol. 173: 2702-2725. https://doi.org/10.1111/bph.13536.

8. Becker-Andre M, et al. (1994) Pineal gland hormone melatonin binds and activates an orphan of the nuclear receptor superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 269: 28531-28534.

9. Romero MP., Garcia-Perganeda A, Guerrero JM, & Osuna C (1998) Membrane-bound calmodulin in Xenopus laevis oocytes as a novel binding site for melatonin. FASEB J. 12:1401-1408. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.12.13.1401.

10. Macias M, et al. (2003) Calreticulin-melatonin. An unexpected relationship. Eur. J. Biochem. 270: 832-840. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03430.x.

11. Martin M, Macias M, Escames G, Leon J, & Acuña-Castroviejo D (2000) Melatonin but not vitamins C and E maintains glutathione homeostasis in t-butyl hydroperoxide-induced mitochondrial oxidative stress. FASEB J. 14: 1677-1679. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.99-0865fje.

12. Acuña-Castroviejo D, et al. (2011) Melatonin-mitochondria interplay in health and disease. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 11: 221-240. doi:10.2174/156802611794863517.

13. Suofu Y, et al. (2017) Dual role of mitochondria in producing melatonin and driving GPCR signaling to block cytochrome c release. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 114: E7997-E8006. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1705768114.

14. Reiter RJ (1993) The melatonin rhythm: both a clock and a calendar. Experientia 49: 654-664.

15. Stefulj J, et al. (2001) Gene expression of the key enzymes of melatonin synthesis in extrapineal tissues of the rat. J. Pineal Res. 30: 243-247. https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-079X.2001.300408.x.

16. Reiter RJ, Tan DX, Paredes SD, & Fuentes-Broto L (2010) Beneficial effects of melatonin in cardiovascular disease. Ann. Med. 42: 276-285. https://doi.org/10.3109/07853890903485748.

17. Garcia JA, et al. (2015) Disruption of the NF-kappaB/NLRP3 connection by melatonin requires retinoid-related orphan receptor-alpha and blocks the septic response in mice. FASEB J. 29: 3863-3875. https://doi.org/10.1096/fj.15-273656.

18. Chahbouni M, et al. (2010) Melatonin treatment normalizes plasma pro-inflammatory cytokines and nitrosative/oxidative stress in patients suffering from Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J. Pineal Res. 48: 282-289. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-079X.2010.00752.x.

19. Ortiz F, et al. (2014) The beneficial effects of melatonin against heart mitochondrial impairment during sepsis: inhibition of iNOS and preservation of nNOS. J. Pineal Res. 56: 71-81. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpi.12099.

20. Reagan-Shaw S, Nihal M, Ahmad N. (2008) Dose translation from animal to human studies revisited. FASEB J. 22: 659–661.doi:10.1096/fj.07-9574LSF.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

For all articles published in Melatonin Res., copyright is retained by the authors. Articles are licensed under an open access Creative Commons CC BY 4.0 license, meaning that anyone may download and read the paper for free. In addition, the article may be reused and quoted provided that the original published version is cited. These conditions allow for maximum use and exposure of the work, while ensuring that the authors receive proper credit.

In exceptional circumstances articles may be licensed differently. If you have specific condition (such as one linked to funding) that does not allow this license, please mention this to the editorial office of the journal at submission. Exceptions will be granted at the discretion of the publisher.